BOOK OF RHYMES

The Poetics of Hip Hop

By Adam Bradley

248 pp. Basic Civitas Books. Paper, $16.95

“– Nothing more than a moon amongst a constellation of star “

Dremur - Why

“Grind till the sunshine” a simple phrase that means a lot to a young Bronx breed MC, who doesn’t desire the glitz and the glam of the industry. He’s satisfied with being heard. Raised by a single parent Dremur has been dealt his fare share of dilemmas unlike many of his close friends and peers he choose to rise above. His fear of pursuing a music career soon subsided after meeting Donny Goines, an underground MC steady on the rise, who gave him some wise words…”no matter how tired or lazy you feel if you want something you go for it no matter what”. Those words have remained embedded in his mind ever since.

Dremur is humble and down to earth and feels the simple things in life are the best things in life. He loves all things that are artistic from dance, painting, and singing. Dremur understands that music as a career choice can be a very challenging journey but with the right support and the right connections he is ready and willing to face all hurdles.

Dremur is also one fourth of hip-hop group Starvin Rebels, along with J.Haz, Mr. Geronimo and Epiphany Blu. Constantly referred to Kanye for his appearance, Lupe for his flow and Common for his word play, Dremur remains level headed and looks at these artists as people who have created a platform for him to follow.

Although the market is full of dance songs and poppy beats with auto-tuned hooks, his outlook on the game still remains the same. The cliché line would be that Dremur is a breath of fresh air, but to be honest he doesn’t feel that way. “I’m more reminiscent of what was, a reminder to the older cats and real hip-hop heads that lyrical craftsmanship still exist”. He is unsure of where his career will go as an artist but he is an avid believer if you can’t get in one way then you better find another.

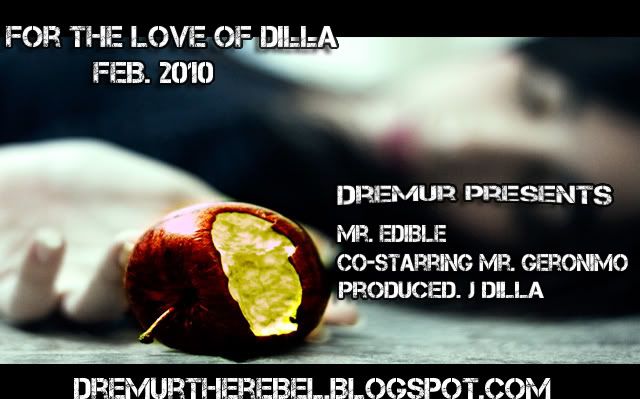

If you have not yet heard of Dremur you soon will, as he continues to grind until his name is a common name on the hip-hop scene. As a writer of feel good music, a lover of art, and all around great guy, Dremur has the motivation, determination, talent and charisma to reach his dream and turn it into a reality. Currently Dremur is working on his first EP, For the Love of Dilla which is slated for electronic release February 2010. He is also working with his group, Starvin Rebels on their debut project as well.

“As an artist I just love the fact that my music could possible make someone feel good, and become motivated to take it to the next level. That’s what I want for people, to find peace, love, and prosperity. That’s why I say that at the end of all my messages because I’m searching for it and so should all my people”

Are you a hip-hop fan who can’t tell assonance from alliteration? An English major who doesn’t know Biggie from Tupac? Adam Bradley’s “Book of Rhymes” is the crash course for you. The book — essentially English 101 meets Hip-Hop Studies 101 — is an analysis of what Bradley calls “the most widely disseminated poetry in the history of the world”: rap, which he rightly says “is poetry, but its popularity relies in part on people not recognizing it as such.”

Bradley, who teaches literature at Claremont McKenna College in California, distinguishes himself from the growing glut of hip-hop scholars by writing a book about rap, as opposed to hip-hop: not a study of the culture or a history of the movement, but a formalist critique of lyrics — almost an anachronistic effort in the era of cultural studies. Like so much work in the genre, though, it’s by and for the already-sold: those interested enough to care whether 50 Cent’s rhymes are monosyllabic or disyllabic, invested enough to wonder why rappers prefer similes to metaphors (because similes “shine the spotlight on their subject more directly than do metaphors,” Bradley says).

To that end, the first half of the book is a triumph of jargon-free scrutiny. Bradley takes on rhythm — from the Greek rheo, meaning “flow,” which is apt: flow is what rappers possess — and dissects rap’s “dual rhythmic relationship,” its marriage of rhymes and beats (with the beat defined as “poetic meter rendered audible”). Next comes rhyme: “the music M.C.’s make with their mouths.” “A skillfully rendered rhyme strikes a balance between expectation and novelty” — e.g., “My grammar pays like Carlos Santana plays,” per Lauryn Hill — and for rappers, rhyme “provides the necessary formal constraints on their potentially unfettered poetic freedom.” The chapter entitled “Wordplay” is the strongest, and that’s appropriate, since play is what hip-hop does best. We’re treated to lyric upon juicy lyric — not just from the usual suspects, to Bradley’s credit — filled with similes, conceits, personification, even onomatopoeia (“Woop! Woop! That’s the sound of da police,” KRS-One rapped).

But the rest of the book disappoints. There are labored discussions of style, that mélange of voice, technique and content; of storytelling (rap has its screenwriters, investigative reporters, memoirists, children’s authors and spiritualists, Bradley notes); and of signifying, otherwise known as swagger, derived from African-American oral traditions like the dozens and the toasts. The author delivers unrevelatory revelations: “All rappers are poets; whether they are good poets or bad poets is the only question.” And he asks questions — “Can rap be both good business and good poetry?”“Why is braggadocio so vital to the art form?” — that have long since been answered by others.

Throughout, Bradley draws surprising connections. Langston Hughes’s 1931 poem “Sylvester’s Dying Bed” is set alongside Ice-T’s classic gangsta track “6 ’n the Mornin’ ”; they employ the same form, and both make ample use of the vernacular. Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” is analogous in structure and storytelling style to the Sugarhill Gang’s landmark “Rapper’s Delight.” Robert Browning’s portentous dramatic monologues are akin to Eminem’s. And the Brooklyn rapper Fabolous’s brusque style earns comparisons to John Skelton’s chain rhyming — which might as well be hip-hop, 16th-century style: “Tell you I chyll, / If that ye wyll / A whyle be styll, / Of a comely gyll / That dwelt on a hyll.” Such parallels are vital to Bradley’s central claim: “The best M.C.’s . . . deserve consideration alongside the giants of American poetry. We ignore them at our own expense.”

But who’s the “we” here? Bradley wants to legitimize rap by setting it in a canonical context, but aren’t we past the point of justifying it? True, CNN is clueless enough to ask, as it did on a 2007 program, “Hip-Hop: Art or Poison?” But no one is really still debating whether hip-hop is a bona fide art form. “Rap rhymes are often characterized as simplistic,” writes Bradley, who admits to finding himself “in the position of defending the indefensible, of making the case to excuse the coarse language and the misogynistic messages.” He needn’t try so hard; in his tone of unwarranted protectiveness, he seems to forget that hip-hop now earns highbrow props worldwide. After three decades, it doesn’t require a defense attorney.

Baz Dreisinger, an assistant professor of English at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, is the author of “Near Black: White-to-Black Passing in American Culture.”